Unmanned and autonomous systems are billed as one of the major force multipliers of the 21st century – across the air, land and sea domains they offer the promise of removing humans from harm’s way. However, the increasing capability of modern cyber warfare and jamming systems raises questions about the limitations of the ‘future of warfare’.

To continue reading the rest of this article, please log in.

Create free account to get unlimited news articles and more!

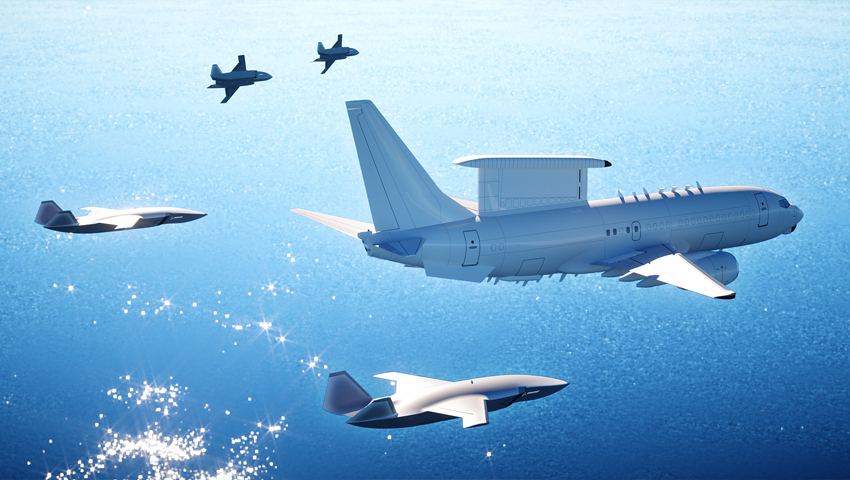

Autonomous and unmanned systems are changing the way the ADF and militaries around the world conduct operations. Supporting combat, humanitarian and intelligence roles, the scope for evolution in these leading-edge capabilities is playing a key role in the development of existing and follow-on systems for Australia and its allies.

Australia's pursuit of a range of autonomous and unmanned systems, including the Northrop Grumman MQ-4C Triton, General Atomics Reaper family of remotely piloted aircraft system (RPAS) and the recently announced Boeing Airpower Teaming System, in conjunction with major modernisation, recapitalisation and multi-domain command and control systems, places the nation at the pinnacle of the global transition towards an integrated fifth-generation and autonomous and unmanned future.

The advent of autonomous and unmanned systems is not solely limited to the air domain, as land and sea systems including platforms like the General Dynamics Multi-Utility Tactical Transport (MUTT) – designed to provide logistics support for infantry – and armed platforms including the proposed US Army Multifunction Utility/Logistics and Equipment vehicle (MULE), and the Kingfish unmanned underwater vehicles and Australian-designed SwarmDiver, become increasingly advanced and prominent in service.

However, as contemporary warfare becomes increasingly dependent on unmanned and autonomous systems, questions need to be asked about the security and practicality of operating such systems in increasingly contested environments challenged by electronic warfare, counter-space and, increasingly, cyber warfare capabilities.

Operating in contested environments

The modern battlefield has rapidly evolved in the last decade. Across the air, land and sea domains, the dissemination of information, ready access to energy and command and control as a result of the increasingly networked platforms and individuals have emerged as the core of the contemporary battlespace.

Recent conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, the Middle East and then more broadly recent confrontations between naval and air platforms in the western Pacific and eastern Europe have served to highlight the limitations of the information, command and control, and energy-centric nature of contemporary platforms and systems.

In particular, the highly successful implementation of electronic warfare platforms like the EA-18G Growlers against the Gaddafi regime and allegations of a successful Iranian cyber attack against the RQ-170 in the mid-2000s that paved the way for Iranian reverse engineering of the then-top secret intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance platform in particular challenges the growing predominant narrative that these unmanned and autonomous systems are to be the undisputed kings of the modern battlefield.

Meanwhile, the growing capability of both state and non-state based actors to prosecute wildly dangerous and effective cyber security attacks on even the most highly defended networks and systems – as was recently committed against organisations including Australian Parliament House and allegations of election tampering in the United States – demonstrate the vulnerability of contemporary systems.

Finally, the growing dependence of contemporary platforms and systems on advanced space-based command and control, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance networks is essential to not only traditional manned platforms but more critically, the unmanned and autonomous platforms that are emerging as key force multipliers in contemporary militaries.

Both electronic warfare and cyber attacks are emerging as the great tactical and strategic levelling forces in the 21st century concept of operations and are dramatically impacting the operating capacity and survivability of unmanned and autonomous platforms in the increasingly contested operating environments of the 21st century.

Human controlled Skynet and 'dead' units

The increasing complexity and potency of cyber warfare capabilities, combined with advanced anti-space and electronic warfare capacities arrayed by both state and non-state actors and the potential for these systems to be turned against Australian and allied systems opens Pandora's Box and questions about the survivability and utility of these increasingly expensive platforms in contested operating environments.

In particular, the increasing cyber warfare abilities of nations like China, Russia and to a lesser extent North Korea and Iran, expose major weaknesses in the defensive and counter-cyber capabilities of Australia and allies like the US to respond and adequately prepare for the potential hacking of these platforms to either neutralise and/or establish control over said systems to turn them against their original operators.

The advent of these capabilities also raises increasingly concerning questions about the security of key intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance platforms and information sharing platforms, and the reliability of these platforms and the information they gather and disseminate. It is important, however, to recognise and identify that autonomous and unmanned systems are not uniquely vulnerable to such attacks, indeed a range of contemporary weapons systems are vulnerable to such attacks, despite their advanced countermeasures.

Maintaining a level of human integration within the operation cycle remains critical to ensuring that these systems remain combat effective and 'friendly' in event of offensive action exploiting the abject and ever present vulnerabilities of contemporary autonomous and unmanned systems.

Get involved with the discussion and let us know your thoughts in the comments section below, or get in touch with

Stephen Kuper

Steve has an extensive career across government, defence industry and advocacy, having previously worked for cabinet ministers at both Federal and State levels.

Login

Login