In the latest Defence Connect Podcast, Assistant Chief Patrick Stewart of the US Border Patrol discussed the impact of geospatial technology on operations and the individuals serving on the front line.

To continue reading the rest of this article, please log in.

Create free account to get unlimited news articles and more!

US Border Patrol’s top priority is to keep terrorists and their weapons from entering the US while welcoming all legitimate travellers and commerce. A role aided by the implementation of geospatial imagery, mobile technology and consistent systems.

In the latest On Point, Assistant Chief of the US Border Patrol Patrick Stewart joins host Phil Tarrant to discuss how the US is utilising technology to implement its security directives at the nation’s borders.

Having joined Border Patrol the day following the September 11 attacks, Stewart will share how that event has changed the way in which they operate, share his thoughts on if technology will advance to a point where human interaction is no longer necessary, and discuss how Australia compares to the rest of the world in terms of border protection.

Phil Tarrant: So you're out here for a conference that you're speaking at, or were speaking at in Canberra I believe. Is it the main thrust of the trip out to Australia or are we here on other purposes as well?

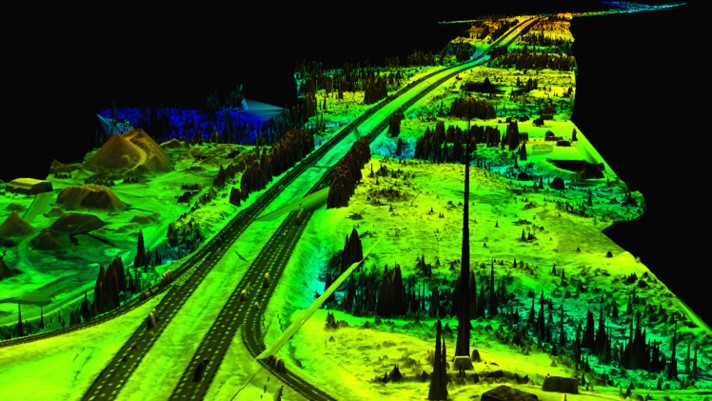

Patrick Stewart: Well that's the main reason. I was here to speak at the Australian Security Summit, specifically to talk about geospatial technologies and how that is improving operations for the Border Patrol.

Geospatial technologies, commonly talked about or referred to as GIS or geospatial information systems. Put in layman's terms, it's the science of where things are. It's understanding the location of items of interest in relationship to the locations of other items that may be of interest, and how other aspects of terrain and environment affect those locations and vice versa.

So, in our case, it is how the location of detections or border patrol agents and other operators, technologies, things like that, where those things are located and how they affect our ability to operate and maintain control of our border.

Phil Tarrant: Okay, can you give me a brief insight into what US Border Patrol does? What is your remit and how wide does it extend?

Patrick Stewart: Sure, so the United States Border Patrol is one of the three uniformed components of US Customs and Border Protection, which is an organisation that just as it sounds, handles customs and border protection aspects for the Department of Homeland Security in the United States. Customs and border protection was established in 2003 after the tragic events of 9/11, and we created the Department of Homeland Security. The Border Patrol however, has been around formally since 1924, so we've been around the block a few times. And we've always had some sort of geospatial component to it, not necessarily with the same technology that we're using now.

But the United States Border Patrol, as opposed to the other uniform components of CBP, we handle all of the space between our official ports of entry. So the United States has roughly 300 ports of entry around the country. Our office of field operations handles that so if you fly into America and you go through customs, and you see the ladies and gentlemen in the blue uniforms that ask you to see your passport and all that, that's our office of field operations. And they handle that activity going through the ports of entry.

The Border Patrol, right now if we're wearing these green uniforms, we handle, like I said, all the space between those ports of entry. The vast majority of that is land border, so it's over 6,000 miles of land border. Both Canadian border and Mexico border. We also have about 2,000 miles of coastal waters around Florida and Puerto Rico, again it's really primarily managing the entry of subjects and contraband coming across the borders, in between those ports of entry.

The way that the border is defined ranges between just simply a swath of land that is cleared across, as an example on the Canadian/United States border. It's just kind of a swath of land and there's border monuments along the way that tell you that you're crossing the border. In some spaces or some places, we have various types of fencing, that ranges between like pedestrian fencing that may be chain link fencing or vehicle barrier fencing, which could be, the best way to describe that, looks like railroad ties that are kind of crossed together. And in some areas we have a more robust fencing pattern, and it just kind of depends on the area and the amount of activity that we have experienced in the past in those areas.

So the neat thing is, if you look at that situation or look at that environment in our geospatial viewer, we have a product that we call the EGIS Map, which is Enterprise Geospatial Information Services Map. We can pull up all of that information. We can see where all of our barriers lie, and the type that it is, how long it's been there. Really kind of give us an idea of exactly what that environment looks like, so if I get temporarily assigned to work at an area of the border that I'm not familiar with, just because they need to pulse up manpower for a short period of time, I can go into that application and see that. Because there is such a wide variance. If I'm coming, as an example, from the northern border with Canada, it's probably coming from an area that's really cold, and distinctly different than the desert in Arizona, as an example. And that allows me to dig right in and take a look around before I get there, and have situational awareness, because of that distinct difference in terrain and the way we protect it.

Phil Tarrant: So if you put innovation into the context of the Border Patrol and geospatial tech that you're using, is that ever going to replace the need for field agents, or it's always just gonna be, and enhances the way they go about doing what they need to do?

Patrick Stewart: You know it's funny, that's always the question, it really is. I don't anticipate the need for human interactivity or interaction on the border to ever go away. There's just too much going on. It's funny because ... part of my program areas is unattended ground sensors and the ground detection capability. And everybody asks me, "What's the perfect sensor?" And my answer to that is, "The perfect sensor is the one, that when you cross illegally, it reaches out and grabs your ankle and gets all your biometric information and writes up the case file for me, and takes you back, so I don't have to interact with you."

Bbut I don't think that we'll ever be in that situation. All it could do I think, or the best that we should hope for it to do, is for it to make our job safer and more effective. If it could do that, it will probably at some point reduce the amount of people that we need to have, but it will never, I don't personally see it as being able to replace us completely. I think we're still gonna have to have agents out there to add that human factor to it. And the big piece of that is, it's difficult for a machine to be compassionate, and despite what a lot of people may think, we're very compassionate people, and we need that aspect. We need to have the human aspect. We're dealing with other humans. We can't expect machines to do it and so we can only hope that it will provide us a safer, more effective environment for us to work in.

So tech has evolved, that's how it's changed. I mean, the threats generally are the same. We've seen obviously the trends have changed and the type of contraband that comes across, or the amounts of contraband changes, and the countries of origin of the people that are crossing. Things like that are to be expected. But the methodologies have changed, based on technology. And it's no different than any other activity. As technology improves, it feeds the improvement of technology, and so the technology increases exponentially. And as that increases, everybody has access to it.

And the thing that we've noticed is that technology increases so fast that, you expect that everybody in the big city might have access to technology, but at some point that technology now rolls over into the people who would normally not be able to afford that technology. So we see that technology coming across the borders, and used to the advantage of people coming across the border, in all aspects. So whether that be technology in the way they conceal drugs, or in the way that they try to evade detection, all of that comes into play. Just the basic cell phone as an example. We are aware of people using cell phones and mapping products, so that they can more rapidly cross the border and evade detection, and there's rumors about people making reports of where the Border Patrol agents are, or set up waiting, and so they'll use that as an opportunity to evade our detection.

So technology works on either side. We have to make sure that we are staying abreast of that, and we have to make sure that we have the cutting-edge technology so that we can make sure that we're a step ahead of all the other guys.

Phil Tarrant: What's the relationship with some of the other federal bodies, so FBI, your intelligence agencies? Is it a pretty close working relationship? I imagine you're the frontline trying to stop a lot of that coming in at a point of entry, or whether that's a designated point of entry or non-designated point of entry. How does that relationship work with the other bodies, the other agencies?

Patrick Stewart: Well so, you're absolutely right about being right there on the front. CBP is the frontline. But, it's important for us to maintain constant communication with these other agencies, and we work very closely, particularly with the other agencies within Department of Homeland Security, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Transportation Security Administration. We work closely with them. We work closely with the Department of Justice, and the FBI, and the DEA, and we have to, because there's just so much going on. If we don't work together as whole of government, it's very hard to get things accomplished.

And so when we put together systems like the GIS system that I came to Australia to talk about, that's a process that we have to make sure we designed in a way that made it easy for us to share data with our partner agencies. That way we're all able to, even if we're not using the same platform, if they're compatible we're able to share data, and it really makes our mission easier to accomplish.

Phil Tarrant: Now you're out here in Australia, and you've been chatting to our Australian colleagues. What are your views on our level of sophistication as a nation in how we protect our borders? We have different scenarios in that we are, we wouldn't have any land borders with anyone. But Australia's a big old place, and we have very porous borders if you think of the north-western Australia and Western Australia. There's hundreds of kilometers of coastline that no one ever sort of sets a foot on, so what's your view on how well we're doing it? Do you think we're behind or do you reckon we've sort of got the right mind set?

Patrick Stewart: Sure, so unfortunately I didn't get a lot of opportunity to kind of survey and review what all you're doing operationally on your borders or for your borders. Obviously my initial experience was my own entry into the country, and the visa process. The process of having that checked as I entered the country, and quite honestly I was impressed with how extensive the application process was, but how streamlined it was, it was very quick. And I understand that that is brand new, that it just literally, that process changed in the middle of July. And so I was lucky enough to have gone through that process immediately after the change, as opposed to my boss who was here just a few weeks ago. Went through the old process, and his description of it, based on what I did, seemed like he went through a little bit, probably several extra steps. I think in the long run, I was very impressed at how comprehensive it was, but at the same time, how streamlined it was.

And then when I arrived, the process was very smooth, getting me through, but I felt like if I was doing something wrong, I should be concerned. But, at the same time, obviously knowing that I wasn't going to have any trouble, it was easy for me to enter. But I mean, everything, everybody had all their ducks in a row, so to speak and it was a nice smooth process. So I think in that regard, I think Australia, it seems like they're doing really good from my kind of outside view looking in.

Talking to some of the people that I've talked to over the week, their use of geospatial technology has apparently been growing considerably over the past several months, and I think they're working with ESRI and they've built a capability in some areas already, and they're working to bring that to the next level where they can share data back and forth, between the various offices within their national components.

I think one of the things that is important for me to share with them, is just our experience when Homeland Security was developed and when Border Patrol was brought into the US Customs and Border Protection, is very similar I think to what has happened here recently with the establishment of Home Affairs. They took a bunch of organisations that already existed and brought them together, and obviously when that happens, each one of those organisations had a way of doing things, and now they have to find a way to continue doing those things, but do them together. But you can't stop in the middle and say, "Let's redo it." You have to continue working. And so that's always a challenge, and that's the same challenge that we went through.

And so specifically with GIS technology, I can speak to the pitfalls that we encountered along the way, and I can say that, "If you're considering this, don't do it, it's not gonna work. You know, we went there, we fell in that hole already and broke our leg, so now that we're healed, we can tell you take this other path. Because it makes more sense and you'll get there faster." And really that's kind of what we're here to do.

I mean that's contingent on whether Australia feels that they need it, and because like I said, that they've already got systems in place and they're already moving down that road, and it's not as much of a matter of, "Hey I have this, you should learn from it." No, it's more of, "Hey, this is what we went through and, maybe it's something that'll help and maybe it won't", and maybe they've already got that handled and it's fine. And we just wanna say, "Hey, we went through this, been there, done that, and we're here to offer our story, basically."

And I think for the most part, Australia is moving down the road pretty rapidly, and I think that they're probably further along than a lot of countries are in that regard. Particularly considering the recent events, and the creation of a new department, and so they may not even really need the assistance. It's more of if I get here and talk to people, and they don't need that advice, that's fine. Then we make contacts and now we've got kind of an open line of communication between the geospatial capabilities of the countries, and if one day I see in the news that "Hey, Australia's doing this great thing with GIS", now I've got some contacts to call and say, "Hey, how'd you guys do that?" And the same thing, now they have a point of contact that if they hear about something else that they haven't done yet, they have someone to reach out to and say, "Hey, how'd you do that?" You know, we're definitely willing to talk shop whenever possible and share lessons learned, however we can.

You can listen to the full podcast interview with Assistant Chief Patrick Stewart of the US Border Patrol here.

Login

Login