We often place a lot of faith in our own intuition when making decisions, but could this be hindering our ability to negotiate effectively?

During World War 2 a gifted statistician was asked to advise the US Army Air Force on where to place additional armour on bombers to protect them from enemy gunfire on raids over occupied Europe. The statistician, Abraham Wald, examined the evidence from surviving aircraft. He calculated the frequency of bullets holes in various parts of the aircraft. His analysis showed that there were significantly more bullet holes in the fuselage than the engine cowlings.

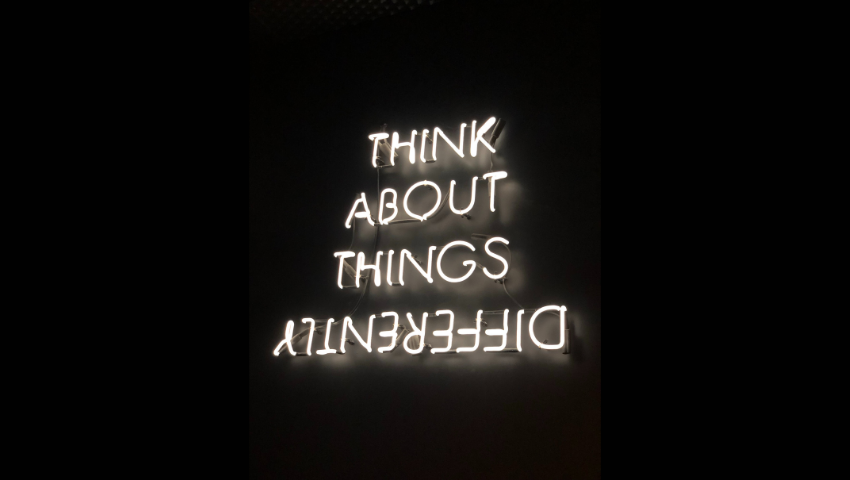

Because additional armour would slow down the planes and require additional fuel loads, the thinking was to concentrate the armour where it would do most good. The initial solution was obvious to the USAAF - concentrate the armour where there were the most bullet holes. Wald thought differently; he thought counterintuitively. He asked, “Where were the missing bullet holes?”(the ones that should have been in the cowlings). If he had a full sample of all the aircraft that were attacked on a mission the bullet holes would most likely be evenly distributed. Wald hypothesised that the missing holes must be in the engines of the planes that did not return; they had sustained critical damage and had crashed. Therefore the additional armour should be on the engines. His advice was adopted for WW2 and the Korean and Vietnam wars.

This counterintuitive thinking should always frame the way we negotiate. Too often our cognitive biases hinder our ability to negotiate effectively. Following a structured, skilled process in negotiation, with mutual gain at the core, compensates for these biases. This is particularly relevant in complex procurement where long-term relationships are established and critical to sustained success. To overcome these natural biases, we first need to recognize them.

The first bias is the zero-sum bias, leading the negotiator to walk into a negotiation with a win/lose mindset, believing that any gain that we make must be an equivalent loss for the other party. This distributive bargaining negates the creativity of negotiators to add value, and to increase the size of the pie before they divide it.

This often leads to the mistaken treatment of information as a source of power which, when withheld from the other party as a result, limits the opportunity to trade where there are value differences between those two parties. The most common trade is price against volume, tenure and/or risk. Those trades cannot occur without the actual volumes, tenure options or risk assessments being disclosed.

A lack of curiosity about the other party’s issues, inhibitions, constraints and concerns often accompanies the lack of disclosure of key information. An intense focus on our own position and issues limits the opportunity for trading and value creation.

As professional negotiators, we advocate for maximum disclosure of what each party wants, what their priorities are, and which areas are non-negotiable. The key questions to determine what should be disclosed are: Will this move the other party towards us or away from us? Will this build trust and encourage reciprocal disclosure by the other party?

Confusing rigidity with strength is also common. A rigid, inflexible position is often brittle. Any move away from initial demands is seen as loss. Skilled negotiators are flexible. They are willing to move away from initial positions in exchange for concessions from the other party. Having too many “must gets” is at the core of this lack of flexibility. There can be many issues in complex negotiations but not all can be mission critical. This can often result in strategic overreach where the detail of how a product or service is to be delivered is unnecessarily detailed and mandated rather than being left to the supplier’s expertise.

A reluctance to drive the negotiating process forward by making realistic proposals is another bias we often observe. This often allows the other party to manage the negotiating process to their advantage. This lack of initiative is often the result of a lack of confidence in our preparation for the negotiation and a belief that the other party will somehow magically guess what is required to get to agreement. When we hear “Give us your Best and Final Offer”, we know that it will be neither.

The negotiating process is deceptively simple. It is knowing what you want and being able to trade in order to get it. Our own biases often get in the way of this simplicity and make the process both complex and problematic. Recognising and harnessing the discipline of a proven process is the key to negotiating successfully.

To discuss your negotiation needs, get in touch with us:

READ MORE

Turning the Tables – 3 Tips for When the Negotiation Power Isn’t in Your Favour

It’s Ok to Leave Some Value on the Table

Obliquity – An Indirect Route to Success

Login

Login