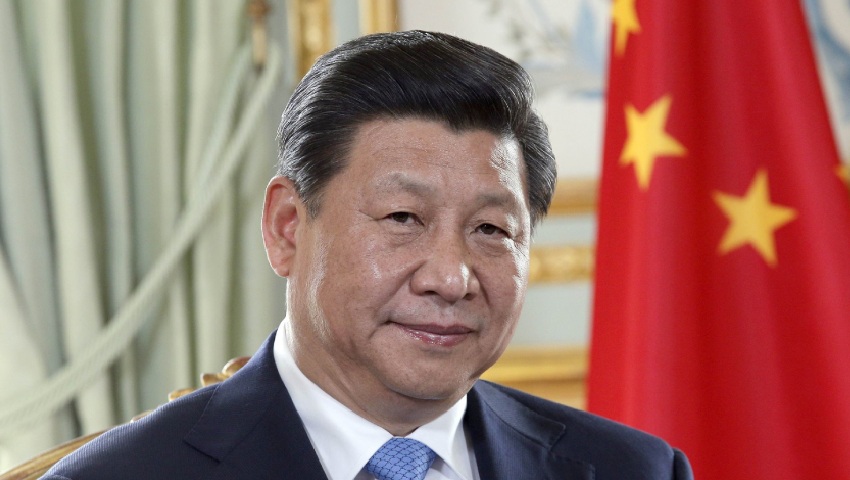

At a video conference in mid-December, Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladmir Putin reiterated their common interests and reaffirmed the political relationship between Russia and China. However, will the relationship withstand military conflict and China’s global ambitions?

To continue reading the rest of this article, please log in.

Create free account to get unlimited news articles and more!

“A new model of cooperation has been formed between our countries, based, among other things, on such principles as non-interference in internal affairs, respect for each other's interests, and determination to turn our common border into a 'belt' of eternal peace and good neighbourliness,” President Putin reportedly told his Chinese counterpart.

Over recent years, China and Russia have expanded their political and social relationships, spurred by a rejection of US primacy and each respective nation’s desire to expand their national borders.

However, it was the growing military cooperation between the two nations throughout 2021 that raised some eyebrows.

In August, Russia and China commenced a joint military drill in China’s Ningxia region which included the participation of 10,000 military personnel, Su-30SM aircraft and even air defence systems. If the images of Russian and Chinese soldiers in embrace were disseminated to provoke Western military analysts, the strategy worked.

Not long after, in October, both nations held naval exercises off the coast of Russia with the Joint Sea 2021 exercise, which the US-based Military Times explained included “anti-mine, anti-air and anti-submarine operations, joint maneuvering and firing on seaborn targets”.

An alliance or a friendship of common interest?

In decades gone, analysts would believe it incomprehensible that China and Russia would not only collaborate with one another on military and economic affairs but collaborate to project joint influence in the region.

For decades following the Sino-Soviet split, the two nations were locked in a competition to exert competitive control over the developing world, gain hegemony over the world’s communist movements and be perceived as the global vanguard for anti-imperialism.

It wasn’t so long ago that the US even tacitly worked with China. Throughout the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, clandestine intelligence units in the US and China would implicitly trade intelligence with one another to the detriment of Soviet forces in the nation.

This implicit co-operation between the US and China to repel Soviet dominance in the developing world was even recognised by the body politic in the West. In the 1984 classic Red Dawn, the Wolverines (a group of high school students who fled into the woods to launch a guerrilla campaign against the invading Soviet forces) were briefed that China and the US fought on the same team against the Soviets.

Eckert: Well, who is on our side?

Colonel Tanner: Six-hundred million Chinamen.

Darryl Bates: Well, last I heard, there were a billion Chinamen.

Colonel Tanner: There were.

While seemingly trivial, such dialogue is indeed important as it is demonstrative of the lens through which the US, Russia and China perceived their relationships toward one another before the turn of the millennium.

Dr Elizabeth Wishnick, professor of political science at Montclair State University, in November unpacked the growing co-operation between Russia and China in War on the Rocks, examining the political realities of their individual and joint efforts in Afghanistan.

“Beijing and Moscow – once bitter adversaries – now cooperate on military issues, cyber security, high technology and in outer space, among other areas ... Some have proposed driving a wedge between the two countries, but this seems unlikely for the foreseeable future,” Dr Wishnick said.

Thus far, Dr Wishnick notes that Russia and China have successfully collaborated to exploit the post-US chaos in Afghanistan, as well as exercising co-operation in neighbouring Pakistan and the broader Central Asian region through the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation.

Indeed, the pair have exercised disciplined joint political messaging on the Afghanistan issue. Recently, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov even asserted that China and Russia remain ready to “jointly manage changes” in the nation.

Such joint messaging has also been evidenced on a legal basis, in which Dr Wishnick argues that “Beijing and Moscow voted against the appointment of a UN rapporteur for human rights issues in Afghanistan. They have also taken some complementary initiatives in Central Asia to boost their individual security co-operation with Central Asian states”.

Nevertheless, the grand strategy of both nations does not perfectly align – especially in their immediate region, with both China and Russia diverging wildly on the relationship with India and the economic coercion enabled by the Belt and Road Initiative.

“China aims to integrate these regions economically into the Belt and Road Initiative, while keeping Indian influence at bay and addressing perceived security threats to the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region,” Dr Wishnick contends.

“By contrast, Russia’s objectives are to maintain its role as the primary security provider in what it sees as the greater Eurasian region and to balance its longstanding ties with India with a new approach to Pakistan.”

In addition to this, while co-operating with China in Afghanistan, Russia has demonstrated more willingness to reach an international and multilateral solution to the Afghanistan crisis than China.

“In a 25-minute speech at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations on October 15, Zamir Kabulov, President Vladimir Putin’s envoy to Afghanistan, suggested a need for a broader negotiation process led by the United Nations. Notably, he did not discuss working with China.”

Perhaps one of the largest areas in which Chinese and Russian foreign policies diverge is regarding the status of India. Despite India’s deep and mutual military relationship with the US, India has nevertheless been an effective and longstanding ally and trading partner of Russia.

In December, India and Russia entered into four new military deals. According to The Indian Express, of those deals:

- Russia approved a joint venture for the production of some 600,000 AK-203 rifles in India’s Uttar Pradesh;

- The two countries would cooperate on military technology until 2031;

- Ratified the Protocol of the 20th India-Russia Inter-Governmental Commission on Military and Military Technical Cooperation.

Even more surprising, last month India even confirmed that they had begun receiving deliveries of the Russian S-400 missile defence system. To give context, Russia even rejected Iran’s request for the purchase of S-400 missile systems, perceived by many as a world leading surface-to-air missile.

Needless to say, the S-400 is an interesting purchase for a member of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, demonstrating not only Russia’s deep and enduring ties with India, but also Russia’s willingness to arm China’s avowed adversaries.

While analysts do typically believe that the US and Indian relationship is becoming India’s pre-eminent geopolitical alliance, ongoing overtures from the Russian government to their long-term ally and partner in India are demonstrative of the fact that Moscow is not willing to curtail their traditional alliances and partnerships to satisfy Beijing.

This perception that China and Russia’s relationship is one of common interest – rather than a military alliance – was shared by Professor Angela Stent of the Center for Eurasian, Russian and East European Studies at Georgetown University, speaking on CNBC’s Squawk Box Asia last month.

“I think both sides recognise, Putin knows, that if he invaded Ukraine, China [isn’t] going to send military help,” Professor Stent said to CNBC.

“But they’ll remain completely neutral and that allows them to do whatever they want in what they consider to be their sphere of influence.”

Your say

China and Russia have begun demonstrating a willingness to cooperate militarily, conducting joint military exercises throughout 2021. However, both nations diverge in key areas.

Considering the evidence of diverging opinions on India, the Belt and Road Initiative and Russia’s (even if in name only) multilateral approach to Afghanistan – it seems likely that the Russian and Chinese collaboration may indeed be a short-term partnership to stave off a common threat.

As always, please join the conversation in the comments section below.

Get involved with the discussion and let us know your thoughts on Australia’s future role and position in the Indo-Pacific region and what you would like to see from Australia's political leaders in terms of partisan and bipartisan agenda setting in the comments section below, or get in touch with

Login

Login