Executive director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Peter Jennings, has called on Australia’s leaders to place more value on northern Australia to fully prepare the nation for an era of renewed great power competition.

To continue reading the rest of this article, please log in.

Create free account to get unlimited news articles and more!

Since the nation’s earliest days, Australia’s strategic and defence planning has been intrinsically defined and impacted by a number of different yet interconnected and increasingly complex factors, namely:

- The benevolence and continuing stability of its primary strategic partner;

- The geographic isolation of the continent, highlighted by the “tyranny of distance”;

- A relatively small population in comparison with its neighbours; and

- Increasingly, the geopolitical, economic and strategic ambition and capabilities of Australia’s Indo-Pacific Asian neighbours.

While the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War cemented America’s position as the pre-eminent world power, this period was relatively short-lived as costly engagements in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Peacekeeping interventions in southern Europe and enduring global security responsibilities have drained American 'blood' and 'treasure', eroding the domestic political, economic and strategic resolve and capacity of the US to unilaterally counter the rise of totalitarian regimes and peer competitors in both China and Russia.

Further compounding these factors, the broader economic, political and strategic rise of Indo-Pacific Asia further challenges the US and its ability to secure Australia’s strategic interests.

This has served to directly conflict with the nation’s long-held belief that it will never really need to do its own heavily lifting in a tactically and strategically challenging environment – further adding to this emerging situation is Australia’s comparatively small population and large geographic area, which led to the 1987 Dibb review and the introduction of the Defence of Australia policy, which shifted the nation’s focus towards continental defence through the narrow 'sea-air gap'.

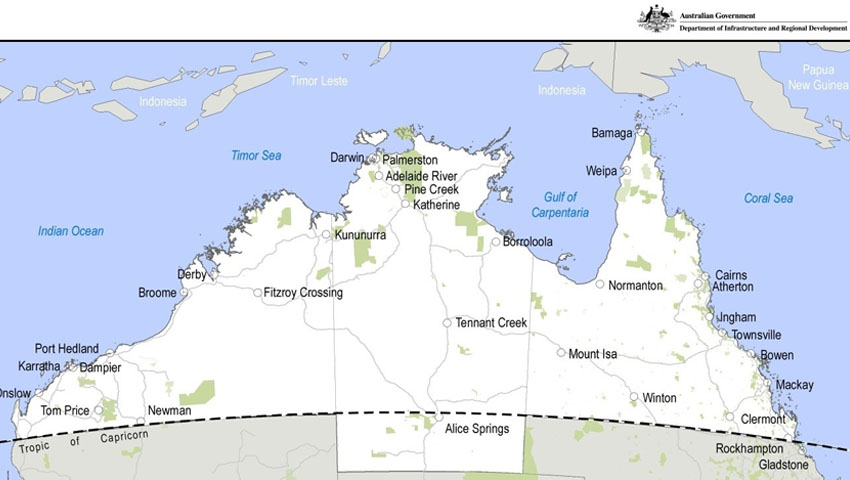

Recognising the increasingly important role northern Australia will play in the future force posture, economic, political and strategic engagement of the nation with its Indo-Pacific neighbours, executive director of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Peter Jennings, has used a piece for The Australian to stimulate public debate and policy approaches to northern Australia.

"It has been painfully obvious for years that our major ally, the US, major regional partner, Japan, and our major market, China, all see more strategic value in northern Australia than successive federal governments and much of our Defence establishment," Jennings states, establishing the long-term international focus northern Australia receives and its role in a period of great power competition.

These comments echo similar points made by John Coyne of ASPI, who wrote a special report for ASPI, titled 'Strong and free? The future security of Australia's north'.

"In terms of Australia’s first, and primary, strategic defence objective – 'to deter, deny and defeat any attempt by a hostile country or non-state actor to attack, threaten or coerce Australia’– it seems that Paul Dibb’s 1986 review of defence capabilities was prophetic. Dibb’s assessment is as accurate now as it was 33 years ago: ‘There are risks inherent in our strategic environment that could pose difficult problems for the nation’s defence.’ Australia has since become key political, economic and military terrain in a new era of major-power competition," Coyne states in his opening executive summary.

A lot of talk, not a lot of action

Both Jennings and Coyne identify that while there is domestic bipartisan support regarding the importance of northern Australia, the action has often been lacking, resulting in underdeveloped infrastructure and economic potential when compared with the broader Australian economy.

"Since January 1901, there’s been fierce bipartisan agreement on the importance of the north to defence and national security. Unfortunately, there hasn’t been the same level of agreement or clarity on the specifics of the north’s critical role in contributing to the broader security of Australia. The perceived imminent threat of a Japanese invasion during World War II eventually brought some clarity in thinking about the importance of the continent’s strategic geography," Coyne posits.

This statement reinforces Jennings' comment about the way in which Australian political and strategic leaders have viewed northern Australia when compared with broader regional and global actors.

Jennings in particular identifies the increasing importance placed upon northern Australia and Darwin in particular by key regional and global allies, namely Japan and the US as both seek to counter the increasingly assertive and disruptive rise of China.

"In the face of a more aggressive China with stronger military forces, the US is dispersing its own forces in Asia. While it’s right to say that 2,500 marines is hardly a threat to Beijing, it’s an important demonstration of America’s commitment to Australia and south-east Asian security," Jennings articulates.

"Strategic thinkers in Japan see northern Australia and Darwin as being an essential part of Japan’s long-term energy security. China can effectively shut down air and maritime transport through the South China Sea any time it chooses. This is an existential threat to Japan because of its dependence on oil shipped from the Middle East. Tokyo needs energy delivery options that avoid the choke point of the Strait of Malacca and Beijing’s control of the South China Sea."

Shifting the focus directly to China's growing influence in the region, Jennings states, "China has been working to cement its dominance in the Indo-Pacific. Far from just being about trade and investment, Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative is a plan to dominate the region’s critical infrastructure, exclude competitors and build economic dependence to the point that political acquiescence follows.

"Just like the fast-food advertisement, the Chinese Communist Party’s strategy is to get regional countries to shut up and take the money.

"The combination of greed and strategic sleepiness that allowed a Chinese company in 2015 to lease the Port of Darwin for 99 years was a grudging wake-up call in Canberra. Half a decade on, it is to the Morrison government’s credit that the penny has dropped on the danger of over-dependence on China."

Each of these points demonstrate the growing importance of the continent's north.

Expanding Australia's northern defence infrastructure

Recognising this, Jennings issues a rather pointed statement directed at Australia's political and strategic leaders and their apparent inaction in northern Australia, stating, "Canberra should also significantly sharpen its thinking about Defence and northern Australia. For its own myopic reasons, the Defence Department has, frankly, wanted to reduce its footprint in the north. In fact, the opposite must happen."

This echoes the central premise of Coyne's thesis, which is the growing need for consistency in policy and planning, particularly around the vastly underdeveloped defence infrastructure, services and, critically, hardening of sensitive infrastructure to support both Australian and allied operations as they become increasingly frequent in an effort to counter the challenges to the regional rules based order.

As greater US forces continue to rotate into the Indo-Pacific. US military assets, particularly large force structures like carrier and expeditionary strike groups, deployed bomber forces and forward deployed expeditionary land forces, will require greater access to reliable and secure basing, maintenance and sustainment infrastructure and facilities – providing a range of local economic benefits.

The dispersed nature of the Northern Territory defence infrastructure, combined with the large-scale basing requirements of forward-deployed US military assets, provides an opportunity to hit reset on key defence infrastructure.

This requires specialised infrastructure development, particularly accommodations, ship mooring and basic, and in some cases in-depth, maintenance and sustainment and airfield requirements – to develop a series of joint military facilities capable of supporting long-range, sustained combat operations throughout the Indo-Pacific.

An example of this could include the major redevelopment of naval facilities in Darwin to accommodate both Australian and American expeditionary strike groups, with specialised moorings to accommodate a US Navy Nimitz or Gerald R. Ford Class supercarrier and supporting naval task group – providing an alternative basing arrangement to the comparatively vulnerable facilities existing in Japan and Guam.

The unique requirements of these facilities also provide opportunities for the long-term development of a domestic Australian nuclear energy industry with the potential for introducing nuclear-powered submarines.

Building on this, the increasing role of the US Marines and their amphibious expeditionary strike groups and corresponding multi-domain combat elements will require increased accommodation and basing facilities beyond the existing Larrakeyah and Robertson Barracks facilities.

Meanwhile, the continuing importance of air power and the increasing rotation of air combat platforms would also require extensive upgrades and modernisation for RAAF Base Tindal, which would assume all the air combat basing and operational responsibilities of RAAF Darwin – consolidating defence capability and providing avenues for developing defence industry 'centres of excellence' providing additional long-term economic benefits.

These points are reinforced by Jennings, who states, "A larger and more visible military presence across the north is needed to protect our offshore oil and gas industry and to assert sovereign interest in a crowded and contested region.

"In Darwin, the strategic need will be to invest in bigger and more capable Defence basing. We should work with the US to grow its Marine Corps presence.

"A larger Defence presence in the north would position Darwin as a security hub, lending confidence in the region and counteracting China’s attempts to dominate and demoralise the neighbourhood."

Recognising this growing operational and strategic need, Coyne presents the need for developing northern Australia into a Forward Operating Base (FOB) North with a focus on hardening, expanding and integrating the critical defence infrastructure across the vast expanse of northern Australia:

"Traditionally, an FOB is a small, rarely permanent base that provides tactical support close to an operation. In the context of this report, the FOB North concept requires northern Australia and its defence infrastructure to be in a state of readiness to support a range of defence contingencies with little advance warning. In this model, RAAF Scherger, RAAF Curtin and RAAF Learmonth need to be much more than bare bases."

Your thoughts

The nation is defined by its relationship with the region, with access to the growing economies and to strategic sea lines of communication supporting over 90 per cent of global trade, a result of the cost-effective and reliable nature of sea transport.

Indo-Pacific Asia is at the epicentre of the global maritime trade, with about US$5 trillion worth of trade flowing through the South China Sea and the strategic waterways and choke points of south-east Asia annually.

For Australia, a nation defined by its relationship with traditionally larger yet economically weaker regional neighbours, the growing economic prosperity of the region and corresponding arms build up, combined with ancient and more recent enmities, competing geopolitical, economic and strategic interests, places the nation at the centre of the 21st century’s “great game”.

As a nation, Australia is at a precipice, and both the Australian public and the nation’s political and strategic leaders need to decide what they want the nation to be – do they want the nation to become an economic, political and strategic backwater caught between two competing great empires and a growing cluster of periphery great powers?

Or does Australia “have a crack” and actively establish itself as a regional great power with all the benefits that entails? Because the window of opportunity is closing.

Get involved with the discussion and let us know your thoughts on Australia's future role and position in the Indo-Pacific and what you would like to see from Australia's political leaders in terms of hardening and enhancing the capabilities of northern Australia in the comments section below, or get in touch with

Stephen Kuper

Steve has an extensive career across government, defence industry and advocacy, having previously worked for cabinet ministers at both Federal and State levels.

Login

Login