Will the looming departure of the Japanese prime minister undermine Australia’s regional security posture?

To continue reading the rest of this article, please log in.

Create free account to get unlimited news articles and more!

Amid ongoing scrutiny over his handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and questions over the integrity of his office, Japanese Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide recently announced he would not serve as leader of the Liberal Democratic Party following the upcoming leadership election.

PM Suga becomes the second Japanese prime minister to step down in less than a year, after his predecessor Abe Shinzo resigned in September 2020.

According to Tom Corben, a research associate in the foreign policy and defence program at the United States Studies Centre, Japan’s leadership instability risks undermining the country’s “competitive edge” in the Indo-Pacific.

This, Corben writes, could pose significant problems for Canberra, with Japan often plugging holes left by “persistent shortcomings” in the United States’ regional strategy.

“Until the long-promised US rebalance to Asia truly materialises, if it ever does, the fact is Australia still needs a Japan capable of playing a major leadership role in the Indo-Pacific,” he explains in ASPI's The Strategist.

“… The risk now, however, is that persistent shortcomings in US Indo-Pacific strategy will compound with a sustained period of political bloodletting in Tokyo, with potential consequences for Japan’s regional strategy.”

Corben notes that PM Suga was expected to deliver foreign policy continuity, continuing the strategic agenda championed by Abe.

Since assuming office, PM Suga sustained Japan’s understated engagement in south-east Asia and strengthened the country’s public posture on Chinese aggression.

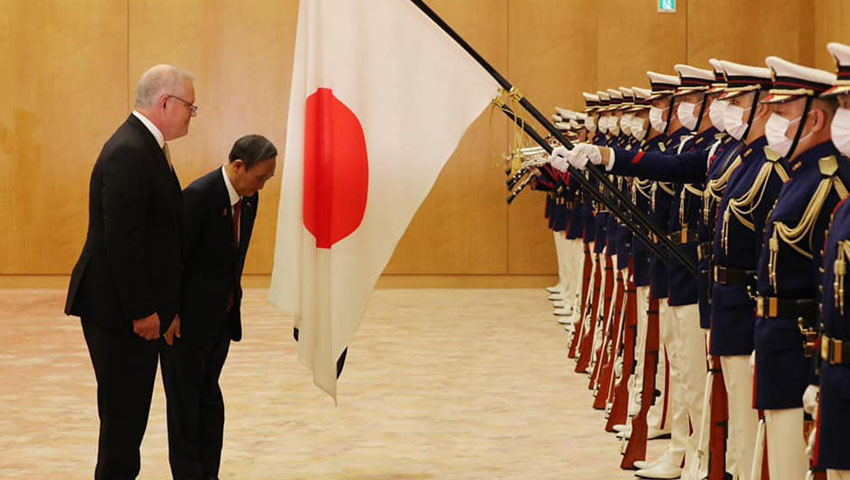

The outgoing prime minister has also sought to build ties with Canberra, highlighted by Prime Minister Scott Morrison being the first foreign leader to visit PM Suga in Tokyo.

While acknowledging that a change of leader is unlikely to lead to an overhaul of the country’s geostrategic policies, Corben warns that frequent leadership changes could “dull Japan’s edge in regional competition with China” and “stall developments in key relationships”.

“It will not be a positive development if ministers who have paid particular attention to Australia, such as Defence Minister Kishi Nobuo, are replaced,” he continues.

With PM Suga’s departure coming just months ahead of a general election, Corben fears that a reduced Liberal Democratic Party majority would hinder plans to bolster defence capabilities, including the acquisition of pre-emptive long-range strike missiles.

“Tighter political margins may hamper the sorts of self-strengthening initiatives that enhance Japan’s strategic value to partners like Australia,” he writes.

“The challenges that awaited Suga as he entered office — a worsening public health crisis, perennial economic stagnation, acute demographic decline — will also confront his successor. Most of these issues are of greater public concern than Japan’s activities abroad.”

But Corben believes there is a “silver lining” for Australia, with PM Suga’s replacement likely to possess greater experience and interest in foreign policy.

The candidates currently touted as PM Suga’s potential replacements, he adds, would be well known to Australian counterparts.

These include Administrative Reform Minister Kono Taro, who served as defence and foreign minister in different Abe cabinets, and is a strong proponent of intelligence-sharing and greater defence cooperation with Australia.

“Kono was outspoken on the threats posed by China before the government’s change in tone and is known for straight talking on tricky issues in the US–Japan alliance,” Corben notes.

“That quality would also be a valuable asset in navigating complex upgrades to the Australia–Japan relationship, such as those proposed by ambassador Yamagami [Shingo].”

Meanwhile, Kishida Fumio, another potential successor, served as foreign minister between 2012 and 2017.

According to Corben, Kishida has previously stressed the importance of maintaining the trajectory of Japan’s Indo-Pacific strategy of strengthening Japan’s defence capabilities.

Corben concludes: “It is in those interests that Japan’s regional partners will hope that whoever emerges as the next prime minister will occupy the Kantei for some time.

“But until that is assured, and until Washington gets its act together in the Indo-Pacific, Australia may yet face uncomfortable questions over the future of the leadership of the regional order.”

Get involved with the discussion and let us know your thoughts on Australia’s future role and position in the Indo-Pacific region and what you would like to see from Australia's political leaders in terms of partisan and bipartisan agenda setting in the comments section below, or get in touch with

Charbel Kadib

News Editor – Defence and Security, Momentum Media

Prior to joining the defence and aerospace team in 2020, Charbel was news editor of The Adviser and Mortgage Business, where he covered developments in the banking and financial services sector for three years. Charbel has a keen interest in geopolitics and international relations, graduating from the University of Notre Dame with a double major in politics and journalism. Charbel has also completed internships with The Australian Department of Communications and the Arts and public relations agency Fifty Acres.

Login

Login