Anyone who has ever worn one of the Army’s standard issue Kevlar helmets will appreciate that they are hot, heavy and mostly uncomfortable, but provide the wearer with a high level of protection.

To continue reading the rest of this article, please log in.

Create free account to get unlimited news articles and more!

But new research by the Defence Science and Technology Group (DST Group) indicates they would provide even greater protection with an additional ceramic layer.

That’s the same hard material as in body armour plates and tank armour.

The DST Group helmet research, published on the DST website last week, followed earlier research on optimising body armour.

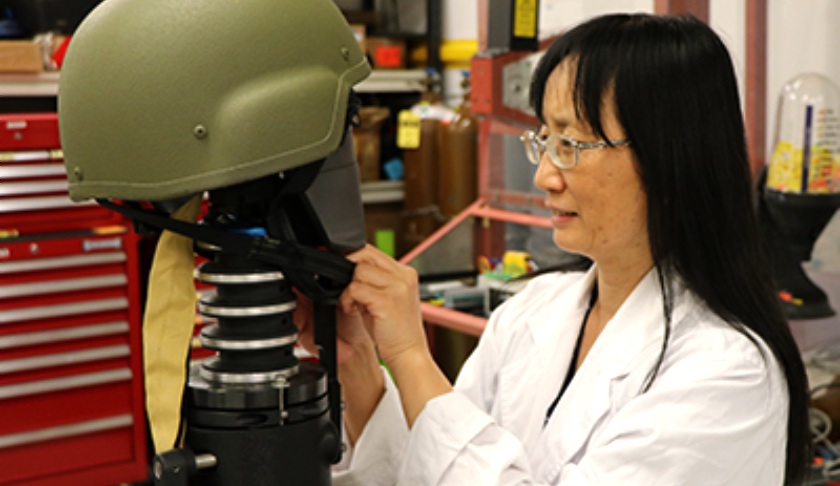

DST researcher Dr Ping Tan said increasing protection while significantly decreasing weight was critical to military helmet function. That could be achieved by optimal helmet configuration and careful selection of materials.

"For this reason, it is important to understand how helmet shells with different material properties, hybridisations and geometries handle various projectile impacts," she said.

"Physical experiments are very expensive, so our aim is to develop a modelling capability to help understand the armour behaviour through computer simulation.”

Dr Tan said this process had developed into a capability to help understand the behaviour of armour material against various blast loadings and ballistic and fragment impact.

The Australian Army pattern of Kevlar helmet is based on the US pattern adopted in the 1980s to replace the M1 steel helmet worn by US troops through WW2, Korea and Vietnam.

These provide the wearer with a substantial level of protection but like body armour won’t protect against any kind of ballistic strike.

Dr Tan said she aimed to predict how a ceramic layer added to Kevlar fibre-reinforced composite helmet shells might improve performance.

Her computer modelling was validated by comparing predicted results with those from earlier theoretical studies and physical experiments.

She found few published studies on modelling and simulation of material properties and configurations for performance of military helmets. There was even less on composite helmets.

“What I have been doing is developing a capability to accurately simulate the ballistics of different, adjoining types of material," Dr Tan said.

Eventually this type of understanding could help develop an Australian industry capability to manufacture curved composite body armour, including helmets.

Her model considered two common types of ceramic – boron carbide, used in tank armour and body armour vest plates, and silicon carbide, used in car brakes and clutches and also vest plates.

Login

Login